Claims that international investigators "suppressed" evidence relating to chemical weapons in Syria have been circulating on social media during the past week. The renewed controversy revolves around two conflicting documents, both emanating from the Organisation for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

The first one is the official report from the OPCW's Fact-Finding Mission (FFM), published in March, which found "reasonable grounds" for believing a toxic chemical had been used as a weapon in Douma last year. It suggested the chemical involved was chlorine gas, delivered by cylinders dropped from the air – implying that the Assad regime was responsible, since rebel fighters in Syria had no aircraft.

The second document is a 15-page internal memo which surfaced on the internet last week after someone leaked it. Written by an employee of the OPCW named Ian Henderson, it contradicts the FFM's findings. In particular, it disputes that the cylinders were dropped from the air and says it's more likely they were "manually placed" in the spot where they were found.

If true, that would support long-standing claims by Russia and the Syrian government that there was no chemical attack in Douma and that rebels planted the cylinders in order to falsely accuse the regime.

Almost immediately after the leaked document appeared, Assad supporters and various conspiracy theorists began claiming that it disproved the FFM's findings and exonerated the regime. Here's one example:

The Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media (which not only defends the Assad regime against accusations of using chemical weapons but also disputes Russia's use of a nerve agent against the Skripals in Britain last year) went further. Noting that Henderson's conclusions were not mentioned in the FFM's report, it claimed there had been a plot to suppress the truth. The OPCW, it said, "has been hijacked at the top by France, UK and the US".

Obviously, the leaked document and the FFM's report can't both be right. While Henderson's document certainly challenges the FFM's findings, claiming that it disproves them is – on current information – a step too far. Similarly, while it's clear that the FFM rejected Henderson's conclusions, the idea that this was done for political reasons is not supported by credible evidence. There could be far less sinister explanations – such as flaws in his analysis.

The problem here is that nobody outside the OPCW knows what internal discussions took place regarding the Douma investigation, and the OPCW isn't saying. That's the way it operates. It investigates quietly and discreetly, and when it eventually publishes its findings it expects the public to trust its expertise. The rationale for working in this way is that it prevents outsiders from interfering but in the internet age it also creates an opening for conspiracy theories about what might be happening behind closed doors.

A question of interpretation

While the fundamental question – about why Henderson's conclusions were rejected – remains unanswered, there are clues about the process by which he arrived at them.

Contrary to the impression given by some Twitter users, Henderson and the FFM were both relying on the same basic evidence. The evidence was compiled by the FFM which carried out on-the-spot investigations in Syria. Henderson's document is labelled as an "engineering assessment" and says its assessment was "conducted using sources of information available to the FFM team".

The dispute, therefore, is about how to interpret the evidence rather than the evidence itself.

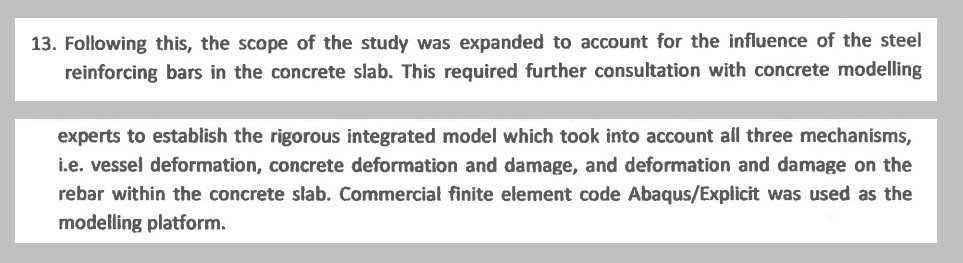

In the case of the cylinders, the FFM's investigation was a highly technical business. It involved complex analysis, including computer modelling, to try to establish whether they were dropped from the air. Details of this analytical process are covered by the OPCW's rules of confidentiality but the FFM's report does give some indications of how its investigators went about the task.

It says the FFM requested three independent analyses from internationally-recognised experts. The experts came from three different countries and had expertise in engineering, ballistics, metallurgy, construction, and other relevant fields. The experts used "different methodologies and approaches for their analyses in order to produce more comprehensive results".

Henderson's "engineering assessment" also made use of experts. It's unclear how many, or who they were, but they seem to have been different experts from those consulted by the FFM. According to the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, "two European universities" were involved.

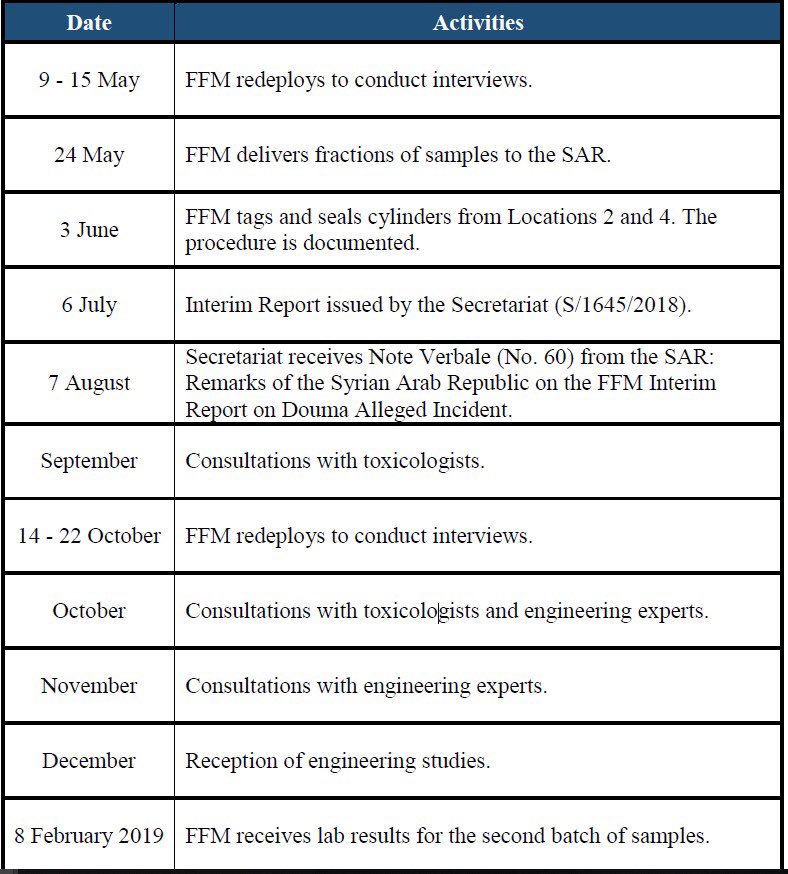

A timeline in the FFM's report shows it was consulting with the chosen experts during October and November last year, and received their findings in December.

There's no information about when Henderson's experts were consulted but the leaked document is dated 27 February this year – just two days before the FFM's report was published and two clear months after the FFM's experts had submitted their findings.

One question this raises is whether Henderson's assessment arrived too late to be considered by the FFM in its report, but a statement issued by the OPCW last week in response to journalists' enquiries appeared to discount that. It said: "All information was taken into account, deliberated, and weighed when formulating the final report regarding the incident in Douma ..."

We also know from the leaked version of Henderson's assessment that it was not the first draft – so when he handed it in on 27 February it's unlikely to have come totally out of the blue.

There's little doubt that Henderson was acting with the knowledge of others in the OPCW. His document is marked "for internal review" and, in the light of the OPCW's confidentiality rules, the fact that he consulted outsiders probably means he had received clearance from above.

A dissenting voice

Henderson's motives for producing his own assessment on Douma are less clear, though it does seem that he was a dissenting voice within the OPCW.

Firstly, the date on the leaked document suggests he knew, at least in broad terms, of the conclusions reached by the FFM's experts, was sceptical about them, and set out to counter them.

Secondly, there are signs that Henderson was critical of the FFM's methodology. The FFM had been trying to establish whether or not the cylinders found in Douma had been dropped from the air. In the leaked document he implies that this was the wrong approach and insists that alternative explanations – such as rebels planting the cylinders – ought to be explored.

When assessing the evidence, he says, it's necessary to develop hypotheses for what might have happened, but this should be done in a way that doesn't "pre-judge the situation or lead prematurely to a mistaken interpretation of the facts". He adds that in preparing his own assessment "an attempt was made to define a set of assumptions and at least two clear opposing hypotheses ..."

Although it's not spelled out explicitly, he appears to be claiming that his own methodology was superior to that of the FFM.

An unlikely whistleblower

If we accept that Henderson was a dissenter within the OPCW, the next question is whether he was a whistleblower too. Was he the person who leaked the document?

On 10 May, David Miller, a professor at Bristol University who is a prominent member of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, posted this tweet:

It's likely that the sender of the anonymous letter was the person who leaked the document, because on the following day the Working Group contacted the OPCW enquiring about Henderson (and was told he had never been a member of the FFM). A couple of days after that, the Working Group posted the leaked document on its website, along with a commentary.

There are several reasons for thinking Henderson was not the leaker.

It's worth noting that the leaked document surfaced 11 weeks after the FFM's report was published – which suggests that someone had only recently found out about it. If Henderson had decided to leak it himself, it would have made more sense to do so much earlier, while the FFM's report was still topical.

Misinformation in the Working Group's commentary also suggests they had no direct contact with Henderson but had been talking to someone else who had scanty knowledge of his work at the OPCW.

The commentary asserted that Henderson was a member of the FFM (despite the OPCW's denial) and had gone to Syria as part of that work. It also asserted that an "engineering sub-group" which helped with Henderson's assessment had been in Douma as part of the FFM.

There's no evidence that any of that is true and the Working Group has not responded to repeated requests via Twitter for an explanation.

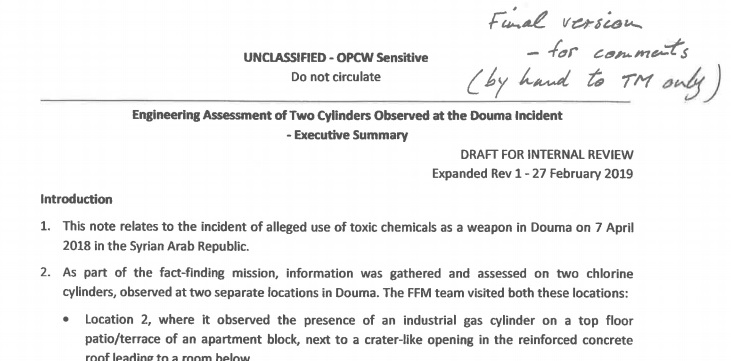

Meanwhile, a handwritten note on the Henderson document suggests that the copy supplied by the leaker had been obtained from one of the document's recipients rather than the author.

The note says "Final version – for comments (by hand to TM only)" and gives rise to a further puzzle. Who or what is TM?

The Working Group's commentary says: "We understand that 'TM' in the handwritten annotation denotes Team Members of the FFM."

A search of the OPCW's website shows "TM" is used in several official documents, but not as an abbreviation for "Team Members". It's short for "Talent Management" – the name adopted by the OPCW for its human resources department.

Since it's unlikely that the human resources department would be interested in Henderson's views on Douma, the most probable explanation is that "TM" represents someone's initials.

- You can view the research for this story via Write in Stone.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed